Beyond the Code

Most software professionals grow up believing that great systems are built by writing great code. After years of working with banks, fintech platforms, national-scale digital systems, and enterprise platforms in Nepal, I have learned a hard truth:

Software projects rarely fail because of bad code.

They fail because the system was never designed to survive the real world.

This realization is what led me to write Beyond the Code.

From writing features to shaping systems

As developers, we are trained to think in terms of:

-

features,

-

tickets,

-

APIs,

-

and sprint goals.

But architecture demands a very different perspective. An architect is not responsible for writing the best function.

An architect is responsible for ensuring that the system itself can grow, change, integrate, scale and remain secure over time.

In simple terms:

-

A developer focuses on how a feature works.

-

A technical lead focuses on how a team delivers.

-

An architect focuses on whether the system will still work next year.

Architecture is not about drawing diagrams. It is about owning the hardest decisions in the system.

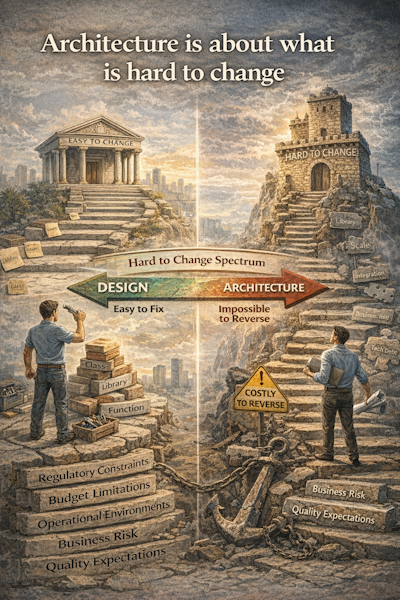

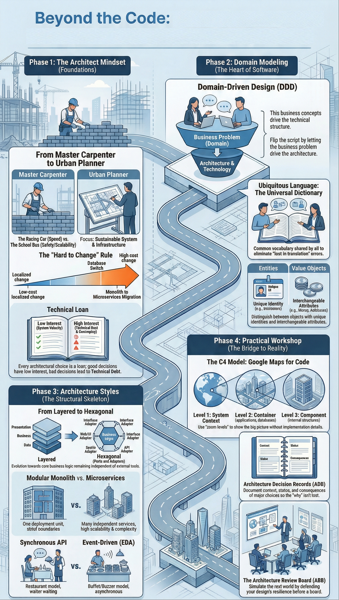

Architecture is about what is hard to change

One of the most important mindset shifts I emphasize in Beyond the Code is the difference between design and architecture. Design decisions are usually easy to fix. Architecture decisions are expensive and sometimes impossible to reverse.

Changing a class structure is design. Changing your deployment model, data architecture, integration strategy or security approach is architecture. If we get these wrong, the project does not fail immediately. It slowly accumulates friction, complexity and technical debt until progress becomes painful.

Real architecture is driven by reality, not trends

Modern technology moves fast. New frameworks, platforms and cloud services appear every month. But architecture is not about choosing what is popular. It is driven by forces such as:

-

regulatory constraints,

-

budget limitations,

-

operational environments,

-

business risk,

-

and quality expectations.

In the market context, this often means dealing with realities such as:

-

data residency and regulatory guidelines,

-

rural connectivity and low-bandwidth environments,

-

limited infrastructure budgets,

-

and high expectations for security in financial and identity systems.

Good architecture does not fight reality. It works with it.

If you cannot model the business, you cannot build the system

Most systems break down not because they are slow, but because they do not reflect how the business actually works. This is where Domain-Driven Design becomes extremely powerful.

DDD is not a technical framework. It is a communication discipline. It helps teams:

-

build a shared language with business experts,

-

divide large systems into meaningful boundaries,

-

and prevent a single massive model from turning into a “big ball of mud”.

When the language used in meetings, documentation and code is aligned, software becomes far easier to evolve.

Structure matters more than scale

One of the most common mistakes I see today is choosing microservices far too early. Microservices solve scale problems.

They also introduce distributed system problems. For most organizations and early-stage products, a well-designed modular monolith delivers:

-

faster development,

-

simpler deployments,

-

and significantly lower operational risk.

Architecture is not about picking the most complex structure. It is about choosing the structure that reduces risk for the business.

Events, integration and boundaries define real systems

As systems grow, communication patterns start to dominate architecture quality. Synchronous API calls create tight coupling. Event-driven approaches allow systems to grow independently. At the same time, edge patterns such as:

-

API Gateways

-

and Backend-for-Frontend (BFF)

become essential to protect internal systems and optimize client experience especially in environments where bandwidth and device constraints are real. Architecture is not only about what happens inside services. It is about how systems meet the outside world.

Diagrams are not decoration. They are engineering tools.

An architect’s ideas are only as useful as their ability to communicate them. In Beyond the Code, I place strong emphasis on practical modeling:

-

using the C4 model to create consistent architectural views,

-

avoiding vague and unlabeled diagrams,

-

and documenting architectural decisions using Architecture Decision Records (ADRs).

A diagram is not a picture. It is a technical artifact. If developers cannot follow it, it is not serving its purpose.

Architecture is risk management

The most important realization in my own career has been this:

An architect is fundamentally a risk manager.

We constantly manage risks such as:

-

over-engineering,

-

premature scalability,

-

fragile integrations,

-

vendor lock-in,

-

and operational complexity.

There are no perfect architectures. There are only trade-offs. The architect’s job is to make those trade-offs explicit — and defend them with clarity.